Martha Graham, the revolutionary American dancer and choreographer, once said, “Theatre is a verb before it is a noun, an act before it is a place.” That phrase has stuck with me ever since I first heard it. I think about it every time I step into a rehearsal hall, crack open a script, or greet a new cast on the first day of a production. Theatre, at its core, isn’t just something you watch. It’s something you do. It is motion. It is energy. It is action.

And the act of making theatre begins long before the first actor sets foot on stage.

It all starts quietly, months in advance. A play or musical is selected as part of an upcoming season. That decision might seem simple from the outside, but it’s rooted in months, sometimes years, of conversation, licensing negotiations, artistic vision, and a deep understanding of what a community wants and needs to see onstage. The selection of a show is the first domino, and once it falls, momentum begins to build.

Next comes the blueprinting. Directors, producers, choreographers, designers, and musicians begin sketching out what this story could look and sound like. Questions get asked: What does this show feel like? How will the set shift? What time period are we anchoring in? What’s the emotional arc for each character? How can we do justice to this work within the confines of our space, time, and budget?

Once auditions are posted, the train really starts to move. Talent shows up—nervous, hopeful, hungry, and a cast is chosen. Rehearsals begin. People who were strangers just days ago start becoming a family. Blocking is set. Songs are learned. Dances are drilled. Lines are stumbled through, then memorized. Mistakes are made. Laughter is shared. Bonds are built. Slowly but surely, the blurry outline of a production becomes clearer.

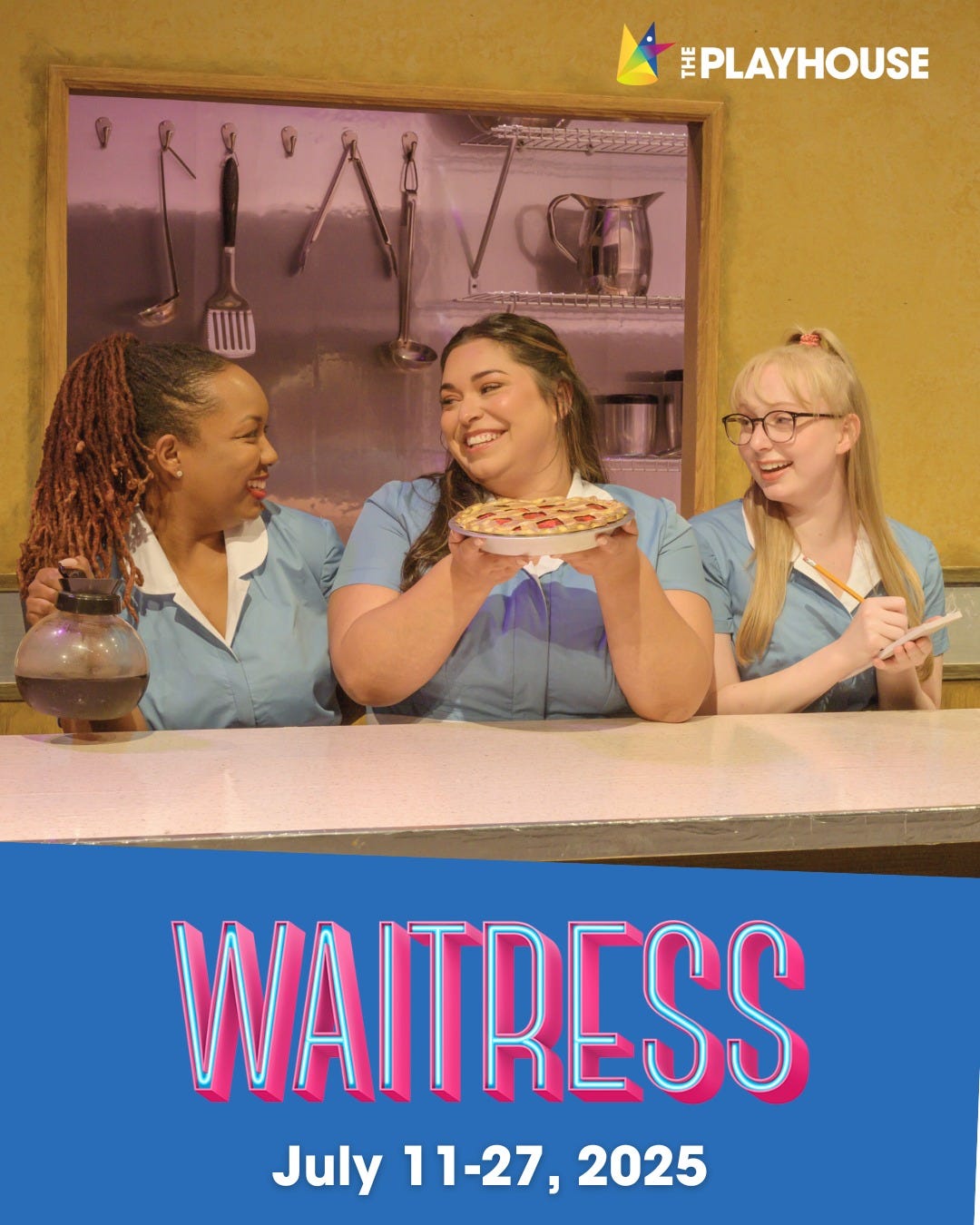

In the case of Waitress, at the Des Moines Playhouse (running July 11–27, 2025), I’ve found myself reflecting more than usual on the behind-the-scenes momentum that fuels community theatre. I play the role of Joe, the grumpy-yet-wise pie diner owner in this musical by Sara Bareilles, based on the 2007 film by the same name. This marks the 28th Playhouse production I’ve been involved in since 1990, whether as an actor, director, backstage volunteer or sound designer, and you’d think by now I’d be used to the process. But I’m not. It still surprises me. And perhaps nowhere is the magic (and madness) more apparent than during one crucial stop along the journey: cue-to-cue.

Let me explain.

Cue-to-cue, often shortened to “Q2Q,” is that magical (and mildly terrifying) moment in the production process when everything comes to a halt. The forward motion we’ve been riding for weeks, rehearsals, music, blocking, dancing, suddenly freezes. And for good reason.

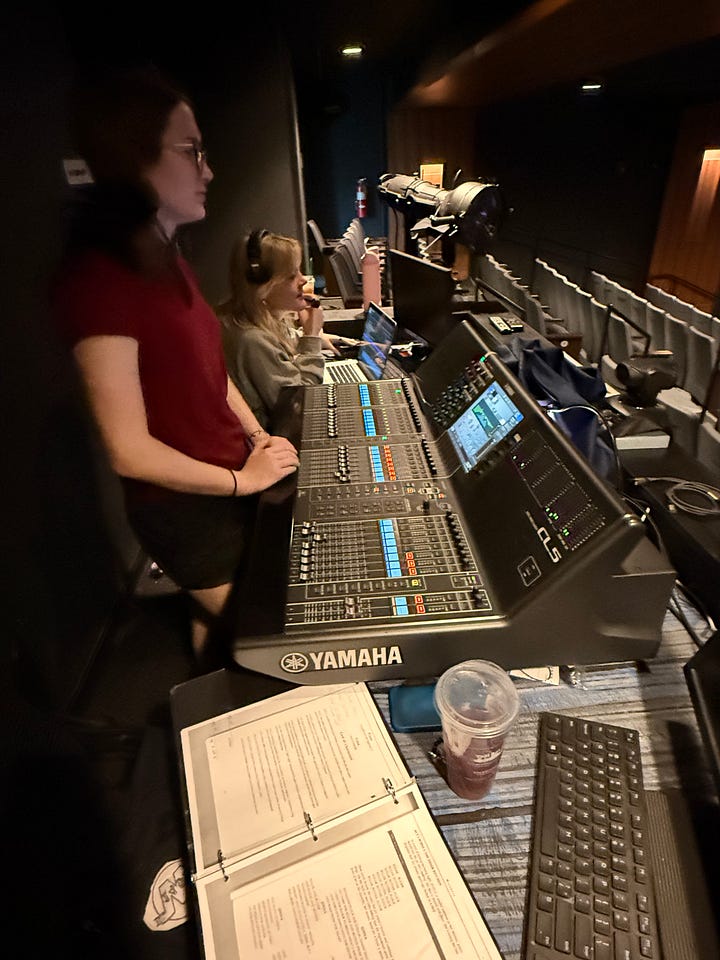

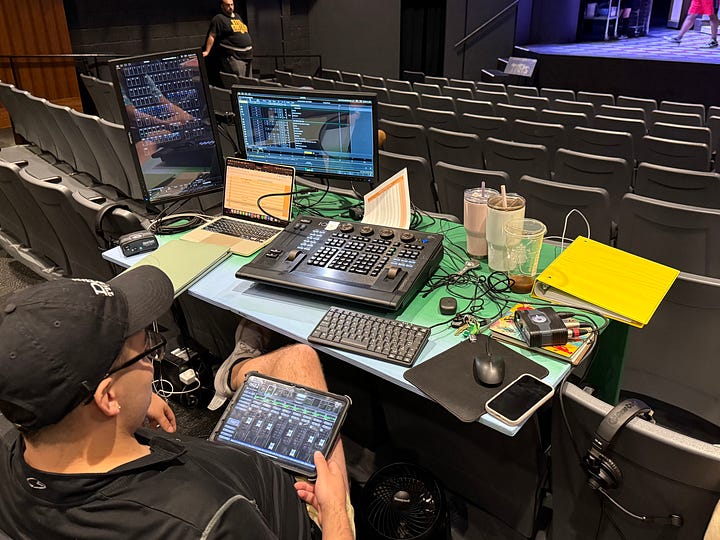

This is the day we painstakingly thread all the invisible strings together. Light cues. Sound effects. Microphone adjustments. Scene transitions. Set changes. Prop handoffs. It’s an all-hands-on-deck and very long day when the director, stage manager, designers, crew, and cast must work together to ensure every technical element of the 112-page script is exactly where it needs to be, down to the second.

For Waitress, that moment came on Saturday, July 5th.

Picture it: the entire cast and crew assembled as we crawl page-by-page through the 112-page script, stopping constantly. “Lights up.” Pause. “Music cue 14.” Pause. “Counter rotates here.” Pause. A pie is placed. A stool is reset. A character walks onstage not to deliver a line, but to check their blocking under a new lighting wash. Over the course of a single day, we applied more than a thousand individual light cues, prop movements, sound effects, and scenic shifts. We haven’t even added costumes, yet! (That comes a couple days later with the first “dress” rehearsal.)

To the outside observer, it might feel tedious—disjointed, even. But it’s absolutely essential. Cue-to-cue is where the show’s rhythm is written into its bones. It’s where you find out just how complicated your show has become. It’s also when the cast realizes, “Whoa—this is the real deal.”

And here’s the thing: while Broadway shows have weeks or even months of previews and out-of-town tryouts to work through these kinks, community theatre productions don’t have that luxury. Our production has 7 days to get back to speed. We don’t have bottomless budgets or endless rehearsal schedules. What we do have is a passionate team of staff, volunteers, designers, and performers who give their nights and weekends to make something beautiful. Somehow, impossibly, it comes together. Every time.

I’ve seen it happen again and again. In the chaos of cue-to-cue, you often get glimpses of the final product peeking through the fog. You see the lights change on an actor’s face during a crucial moment, and you feel a shiver down your spine. You hear the harmonies of a ballad echo in the house for the first time, and suddenly the story feels real. Those moments remind you why we do this.

Community theatre, perhaps more than any other kind, is a labor of love. It’s where servers become leading ladies. Where school teachers become ensemble actors. Where accountants moonlight as set painters. Where young people get their first taste of the stage, and where veterans like me keep coming back because, well, we just can’t help ourselves. We believe in the power of story. We believe in that sacred space between the curtain and the footlights.

And as cue-to-cue fades into final dress rehearsals and eventually opening night, something incredible happens. The friction of stops and starts gives way to fluid motion. We begin to dance, not just literally, but as a full company, in sync. Each tech cue, each blackout, each set shift becomes second nature. The train is moving again. Faster now. Steadier. Until finally, the audience arrives, and the lights go down.

That’s when the magic truly happens.

And all those verbs, the acts of reading, selecting, designing, rehearsing, painting, rigging, adjusting, cueing, finally transform into a noun. Theatre. A place where people gather to laugh, cry, think, and feel. A place where, for two hours, the world outside disappears and we are all transported somewhere new.

So if you find yourself at the Des Moines Playhouse to see Waitress, know that what you’re witnessing is more than just a performance. It’s the result of hundreds of hours of movement. Action.

Theatre may appear to be a finished product. But it is, first and always, an act.

I am a singer songwriter who many years ago auditioned for a part in a local production of The Fantastics and got a minor role. During the fourth or fifth performance I jumped a line and the pro lead actor picked up the flow in a half second.

Maxwell, I just caught up with this terrific piece! Thank you for taking us behind the scenes! I hope you write more about this art form! Community theater touches so many local communities.